The Power of Naming: How Language Shapes Identity and Meaning

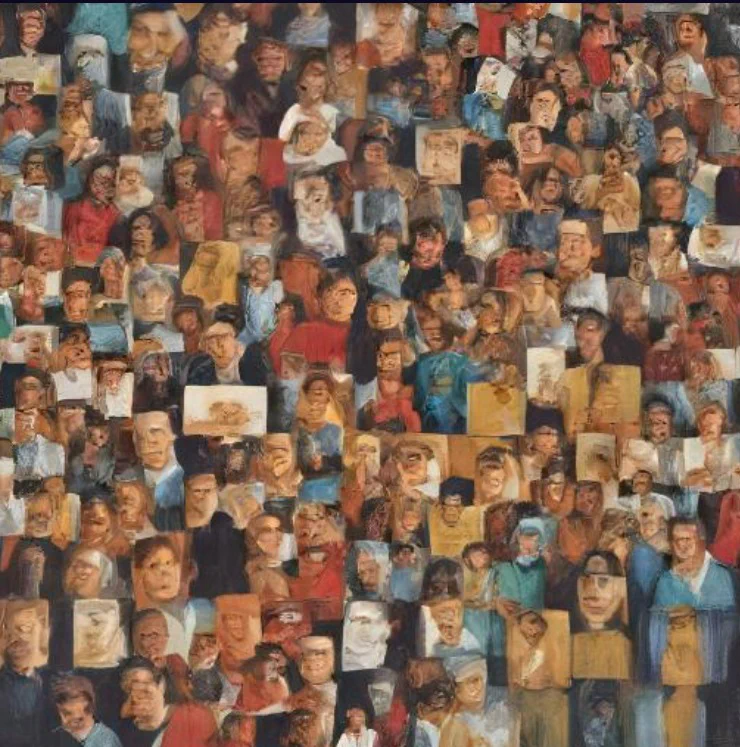

Image credit: Harrison Youn

Image credit: Harrison Youn

The sentence “Harrison is a student” uses “Harrison” as a proper noun referring to a specific person, while “student” is a general term categorizing individuals engaged in academic pursuits. According to Aristotle, proper nouns denote first substances, while general terms refer to second substances. The key distinction between first and second substances is that while a first substance (proper noun) can only function as a subject, a second substance (general term) can serve as both a subject and a predicate. For instance, it is logically possible to say, “Harrison is a human,” but not “Human is Harrison.” However, for general terms like “student,” both “Harrison is a student” and “A student is a human” are valid. This tradition was deeply rooted in earlier language philosophy. Every concept, Aristotle suggested, can be understood through two dimensions: “connotation” and “denotation.” Connotation refers to the qualities a concept implies, while denotation indicates what it refers to. For example, if someone knows that my name is Harrison, they only know the fact that my name is Harrison without any further implied meaning. In this case, the proper noun “Harrison” would carry denotation but no connotation.

However, with the advent of Gottlob Frege, this Aristotelian tradition began to be fundamentally challenged. In his work Uber Sinn und Bedeutung (On Sense and Reference), Frege posited that proper nouns possess not only denotation but also connotation. Frege argued that proper nouns have two functions: the ‘reference’ (Bedeutung) and the ‘sense’ (Sinn). For instance, when someone hears the name “Harrison,” if they know me but are unfamiliar with OSU football, they might think of me, whereas someone who knows about OSU football but not me might think of Harrison Jr., the athlete. By this reasoning, Frege suggested that proper nouns encapsulate both denotation and connotation. However, Frege’s argument holds only when considered from an “ex post facto stance,” meaning that connotations develop based on previously learned information associated with the proper noun. Thus, someone hearing the name “Harrison” for the first time may find it difficult to identify any connotations attached to it.

Frege’s view holds critical significance in the philosophy of language because it introduced the idea that proper nouns can imply predicates. In traditional language philosophy, any proposition involving a proper noun as a subject must necessarily be synthetic; that is, no matter how deeply one examines the proper noun “Harrison,” one cannot deduce whether the statement “Harrison is a student” is true or false, as this truth can only be confirmed through experience. However, if, as Frege contended, the predicate “OSU student” were already implied in the proper noun “Harrison,” we would no longer need to rely on experience to determine the truth of the statement. This idea became the subject of significant debate among many 20th-century philosophers and logicians.

Bertrand Russell, Wittgenstein’s teacher and co-author of the legendary Principia Mathematica with Whitehead, was one such figure. Russell systematized the idea that proper nouns carry connotations through his “Theory of Descriptions.” According to him, proper nouns could be broken down into a set of descriptions. Consequently, all propositions could be treated as analytical propositions. Russell was deeply influenced by Leibniz, especially by the notion that, from the perspective of God, all propositions are analytic. For instance, in the statement “the sum of a triangle’s interior angles is 180 degrees” or “a student is human,” the predicate is already contained within the subject. Thus, when dealing with analytic propositions, once we fully understand the subject, we can determine the truth or falsehood of the proposition without relying on experience. Similarly, Leibniz argued that every entity denoted by a proper noun already implicitly contains all its potential predicates. Of course, such comprehension is only available to God, who created all individuals, and hence is unattainable from a human perspective (the objects Leibniz refers to are also famously known as monads).

Russell took this idea even further, asserting that all proper nouns are merely abbreviations of descriptions, and that denotation does not exist. For instance, someone may have heard of both an athlete and a singer named Harrison, but, without recognizing the individual, might fail to identify the singer if they encountered him. Russell referred to demonstrative pronouns like “this” and “that” as “logically proper names,” asserting that such words, discernible through sensory experience, form the basis for proper names. In this view, a proper noun becomes meaningful only when connotation is added to such empirically distinguishable proper names. By denying the need for denotation in proper nouns, Russell effectively stripped first substances, as defined by Aristotle, of their privilege of functioning solely as subjects. However, Russell’s theory, like Frege’s, is also contingent on an “ex post facto stance.”

Saul Kripke, following in the footsteps of Russell’s student, Ludwig Wittgenstein, and directly opposing Russell’s view that proper nouns are mere abbreviations of a set of descriptions, advanced an “ex ante” perspective in language philosophy. Consider the example of someone naming me “Harrison.” Over time, I might become an athlete or remain a student. Kripke emphasized the significance of the moment when a proper noun is first assigned. He stated:

“In most cases, our act of referring does not depend solely on our own understanding of the subject but also on the history of how the name reached the individual within the language community. By tracing this history, we come to comprehend what the name refers to. One could say that an initial naming ceremony occurs. Here, a real object is directly shown to name the entity, or the referent of the name might be fixed through a description. Nevertheless, when the name is ‘passed from person to person’, those learning the name must use it to refer to the same subject as those who taught it to them. (Naming and Necessity)”

Kripke’s focus on this “initial naming ceremony” reveals his reflection on the prior state of the proper noun’s definition when someone first named me “Harrison.” Over time, those who observed my life as a student might solidify the name “Harrison” through descriptions. Later, if I become a singer, the reference of “Harrison” will be updated accordingly through new descriptions. The crucial point is Kripke’s claim: “When someone receives the name, they must use it to refer to the same subject as those who passed the name to them.” He emphasized that even if the individual designated by a proper noun dies, the proper noun continues to rely on the initial naming ceremony and the historical transmission of the name through a language community.

For instance, the name “Aristotle” has been passed down from the time he was born, became Plato’s student, and later criticized his teacher to form his own philosophy that profoundly influenced Western thought. Even if those who directly or indirectly observed Aristotle are long dead, they would have attempted to convey knowledge of him through oral or written accounts, allowing the proper noun “Aristotle” to reach me, someone raised in Korea. This continuity of transmission through a language community is in stark contrast to Frege’s and Russell’s views, especially since Russell argued that “since we have not encountered Aristotle directly, we cannot name him.” This point formed the crux of Kripke’s critique of Russell. He strongly opposed Russell’s post hoc stance, which ignored the importance of others involved in the initial naming process or those who subsequently learned the name from them.

If Russell defined proper nouns as mere abbreviations of descriptions, Kripke described them as “rigid designators,” because a proper noun is created the moment a name is assigned in an initial naming ceremony. To further undermine Russell’s Theory of Descriptions, Kripke introduced the concept of “possible worlds”:

“Let us suppose that the referent of a name is fixed by a description or a set of descriptions. If the name meant the same as the description, then the name would not be a rigid designator. The name would not necessarily refer to the same object in every possible world. (Naming and Necessity)”

For example, according to Russell’s logic, the descriptions “Aristotle is Plato’s disciple” and “the author of Metaphysics” are nothing more than simple descriptive phrases. It is at this point that Kripke introduces the logic of possible worlds (interpreting this concept through the lens of the future tense can make it easier to understand. Although a proper noun like Aristotle no longer has a future, we, who are living in this present moment, exist within a real future-possible world). In this possible world, Aristotle might not have been Plato’s disciple, nor might he have written Metaphysics. Yet, even in this possible world, we can continue to use the proper noun “Aristotle.” However, we cannot replace “Aristotle” with the descriptive phrases “Plato’s disciple” or “the author of Metaphysics” as subjects in this possible world. Why is that? In a possible world, the proposition “Aristotle is not Plato’s disciple” is usable, precisely because it is a possible world. But if we substitute the proper noun “Aristotle” with the descriptive phrase “Plato’s disciple,” a problem arises. The proposition “Aristotle is not Plato’s disciple” becomes “Plato’s disciple is not Plato’s disciple,” which is a logical contradiction that cannot hold, even in a possible world. For this reason, Kripke criticizes Russell’s logic, which sought to reduce proper nouns to descriptive phrases, stating that while descriptive phrases are limited to specific worlds, “proper nouns must necessarily refer to the same object in all possible worlds.” This is possible because proper nouns function as “rigid designators.” Russell, who was able to collect descriptive phrases through historical information, could offer a retrospective interpretation. However, for someone who is still alive, we cannot pre-determine which descriptive phrases will attach to them in the future. I might quit economics and return to Korea to open a cafe, but Harrison will still be called Harrison.

Like nouns such as “man” or “woman,” common nouns are primarily used to categorize individuals, a practice traceable back to ancient philosophy, such as Aristotle, who based scientific knowledge on classification by species. Unfortunately, inherent in classification is the constant risk of exclusion and violence. Just as many people categorized under the common noun such as “Asian”, “Black”, “Jew” and many others were victims in some parts of our history, those who are stripped of their proper nouns and classified into a certain race or group are reduced to mere objects. This means they are denied their dignity as unique individuals. To affirm a proper noun is to affirm that the individual is an irreplaceable being. This is why we should be grateful to Kripke—whether he intended it or not, his logic offers us the possibility of returning proper nouns to individuals.