Strange Loops and Recursive Realities: Transforming Chaos into Clarity

Image credit: M.C. Escher

Image credit: M.C. Escher

This morning, I had an invigorating conversation with my old friend about the creative innovation behind Palantir’s Foundry Ontology. We were both impressed by its capacity to impose structure on the vast and often chaotic landscape of globally dispersed data—data that, in its raw form, appears lacking in intrinsic meaning. By introducing a novel framework of order, the Ontology transforms this seemingly haphazard information into a coherent system, enabling users to derive actionable insights and causal inferences, thereby amplifying the data’s practical relevance.

One of the most remarkable aspects of the Ontology is its potential to reshape an organization’s value system, pushing it beyond narrow financial objectives. Take the healthcare industry, for example: the Ontology could revolutionize the contentious process of reimbursement negotiations between hospitals and insurance companies. Currently, insurers deny a large proportion of hospital claims for a variety of reasons, often resulting in significant financial losses. Without the Ontology’s intervention, departments tasked with managing these rejected claims must either resubmit or forgo them, a process fraught with inefficiencies.

By leveraging the Ontology, data from different hospital departments is systematically organized, enabling a more nuanced reevaluation of claim denials. For instance, when a claim is rejected for alleged over-treatment, physicians can more accurately assess whether the treatments were truly necessary for optimal patient care—an evaluation that administrative personnel, with their distinct areas of expertise, may have overlooked.This interdisciplinary collaboration fosters a more holistic resolution process, leveraging the collective expertise of different departments to expedite the resolution of denied claims. As a result, hospitals not only improve their financial standing but also transform isolated, fragmented data into a source of synergistic value. Of course, these processes are automated by AI, significantly accelerating the speed of operations as well.

Beyond financial outcomes, the Ontology drives a profound reconfiguration of departmental dynamics. By pushing departments to transcend their habitual workflows, it cultivates an environment where processes evolve to align with the organization’s broader strategic goals. This, in turn, promotes a more unified and efficient operational structure, with departments working in concert rather than in isolation.

This conversation naturally steered us towards the timeless philosophical debate: does mathematics precede empiricism, or vice versa? This question has often animated our discussions, but today we found that the Ontology model represents a compelling inversion of the traditional sequence. In conventional scientific practice—social sciences included—mathematical models impose order by establishing data generating processes (DGP) with a set of reductive assumptions that help us make sense of the real world. Theoretical constructs lead, and empirical work follows to validate these models. In contrast, the Ontology subverts this approach by imposing new, emergent rules on pre-existing disordered data, constantly updating and refining these rules as new data arrives. This creates a dynamic, iterative cycle—once initiated, it continuously evolves.

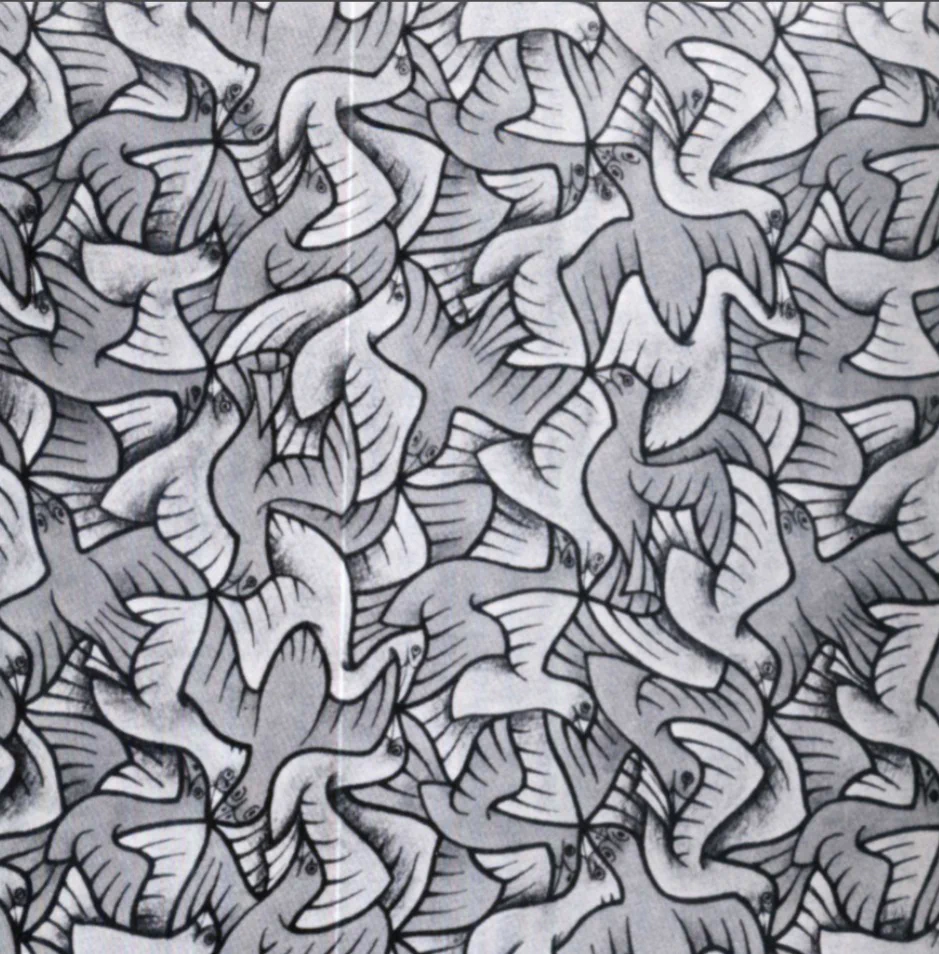

As I reflected on this dialogue, I was reminded of the intellectual stimulation I once found in Godel, Escher, Bach. Hofstadter’s exploration of self-reference and the strange loop, where one returns to the starting point to begin anew, parallels the recursive processes at play in Palantir’s Ontology. It made me wonder: in the context of AI learning autonomously through these loops, who presses the initial enter key to trigger these endless recursions? Is it the chicken or the egg that comes first in this recursive process? With Palantir, when we apply mathematical rules to chaotic data and then update those rules based on new data, do we spark yet another recursion?

This recursive and iterative nature—evident in both Hofstadter’s work and the Ontology—strikes at the heart of how emergent properties in complex systems unfold. Both systems reveal how layers of meaning and order arise from what seems, at first, to be an impenetrable chaos. I must confess, at this point, that Hofstadter’s Godel, Escher, Bach has been one of the most profound influences on the very core of my thoughts—its ideas of becoming resonating deeply with my reflections on chemistry, political theory, causality, and even love, as I’ve explored in my earlier posts.

However, this is not only limited to the recursive iteration vertically. In the horizontal perspective, it also brings an intriguing idea. In my master’s I wrote a short resting paper on reinforcement learning based on Q-learning model. The idea of the Q-learning is in line with the recursive iterations above mentioned but using Bellman equations. However, the underlying idea of this modeling is reward-based model; that people learn from reward but avoid punishment, which makes sense. However, the issue with this is that if learner successfully avoid the punishment, in the next iteration, the probability to choose the previous punishment decreases. With many iterations, the model’s prediction converges to the best expected rewards as the bellman equation does but the probability of choosing previous punishment updates towards zero. Do we never learn lessons from our mistake? This was what I was curious in this reinforcement learning when Godel, Escher, Bach showed me the figure above with this description:

“When a figure or “positive space”… an unavoidable consequence is that its complementary shape-also called the “ground”, or “background”, or “negative space”- has also been drawn. … Let us now officially distinguish between two kinds of figures: cursively drawable ones, and recursive ones. A cursively drawable figure is one whose ground is merely an accidental by-product of the drawing act. A recursive figure is one whose ground can be seen as a figure in its own right. The “re” in “recursive” represents the fact that both foreground and background are cursively drawable - the figure is “twice-cursive.” Each figure-ground boundary in a recursive figure is a double-edged sword. M.C. Escher was a master at drawing recursive figures… There exists recognizable forms whose negative space is not any recognizable form. In more “technical” terminology, this becomes: There exist cursively drawable figures which are not recursive. If you read both black and white, you will see “FIGURE” everywher, but “GROUND” nowhere. “

Interestingly, in my short presentation years ago, it turned out that, through the lens of Bellman equations, people can learn from their mistakes just as they do from rewards. This raises a question: what, then, is the true relationship between rewards and punishment—what stands in the foreground, and what fades into the background? As the figure above illustrates, the answer lies in where we choose to direct our gaze.